That “safety” harness you bought on Amazon is a marketing lie that will catastrophically fail in a real crash, turning a simple restraint into a projectile.

- Crash physics multiply forces exponentially; a 50 lb dog becomes a 1,500 lb projectile at just 30 mph.

- Extension tethers and ziplines allow for dangerous momentum build-up, guaranteeing system failure at the moment of impact.

Recommendation: Discard any product not certified by the Center for Pet Safety (CPS). Verifiable, independent crash testing is the only metric for survival, not marketing claims.

The decision to restrain your dog in the car feels like a responsible one. You browse online, find a highly-rated “safety harness” or seatbelt tether, and believe you’ve protected your companion. From an automotive safety engineering perspective, this belief is not just wrong; it’s dangerously misplaced. The market is flooded with products that use the word “safety” as a hollow marketing term, providing a fatal illusion of security while completely ignoring the fundamental physics of a collision.

Most pet owners think in terms of simple restraint—preventing a dog from jumping into the front seat. Engineers think in terms of managing catastrophic kinetic energy. In a crash, it’s not about holding your dog in place; it’s about decelerating thousands of pounds of force without the equipment snapping, the anchor points ripping out, or the harness itself inflicting lethal injury. The difference between a product that accomplishes this and one that fails is not semantics; it’s the verifiable, independent testing protocol established by the Center for Pet Safety (CPS).

This analysis is not a product review. It is a critical look at the engineering principles that dictate whether your dog lives or dies in a car accident. We will dissect the forces at play, evaluate the structural integrity of restraint systems, and provide the non-negotiable criteria for selecting equipment that offers a genuine chance of survival. Forget the star ratings and marketing copy; understanding the physics is the only way to make a truly informed choice.

To fully grasp the critical differences between marketing claims and engineered safety, this guide breaks down the core physical principles and practical considerations. The following sections will equip you with the knowledge to evaluate any pet travel restraint system like a safety engineer.

Summary: A Physics-Based Approach to Canine Car Safety

- Why Extension Tethers Become Projectiles in a 30mph Crash?

- Isofix vs. Seatbelt Loop: Which Anchor Point Is Stronger?

- The Front Seat Risk: Why Pets Should Never Ride Shotgun?

- Crate or Belt: Which Is Safer for Large Dogs Over 80 lbs?

- When to Replace a Safety Harness After a Minor Fender Bender?

- Why Harnesses Crossing the Shoulders Restrict Movement?

- From Vomit to Joy: Conditioning a Dog to Ride in the Car

- Y-Harness vs. No-Pull: Which Prevents Shoulder Injuries in Pullers?

Why Extension Tethers Become Projectiles in a 30mph Crash?

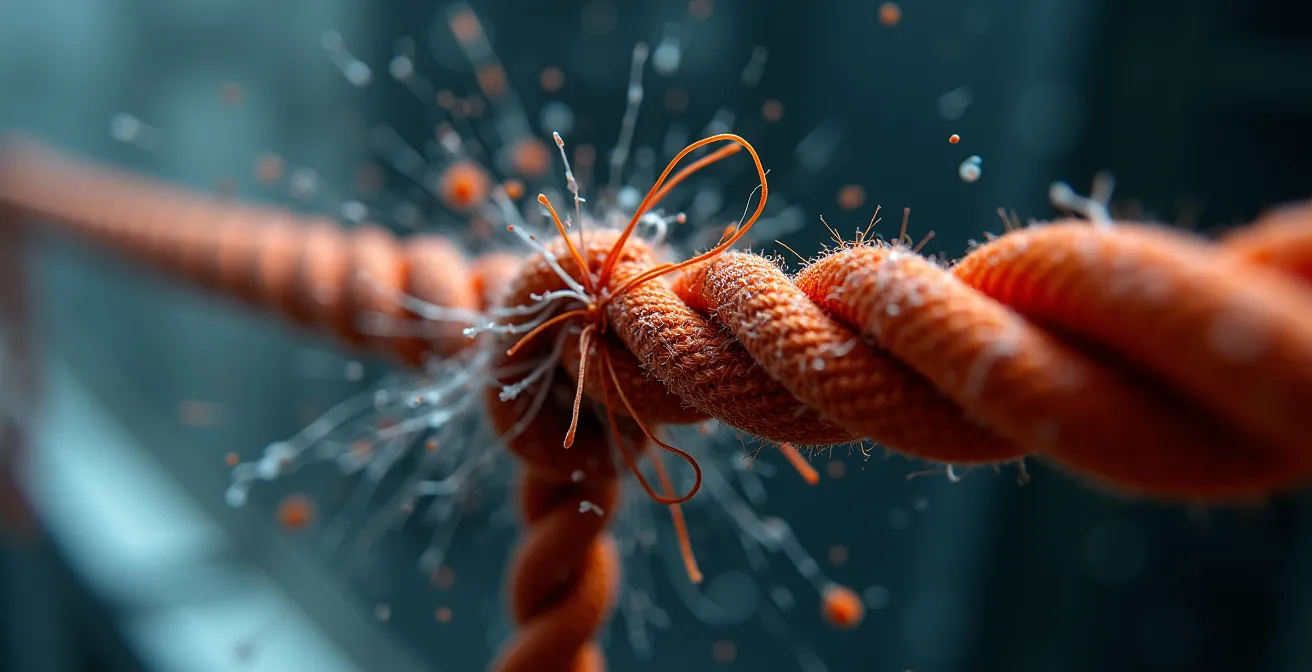

The most common and dangerous misconception in pet travel safety is that any restraint is better than no restraint. This logic collapses when confronted with the physics of an extension tether—the long straps of webbing that clip a harness to a seatbelt anchor. These devices create a deadly “slingshot effect” by allowing a dog to build up immense kinetic energy before the restraint engages.

Consider the forces involved. In a collision, an object’s effective weight is multiplied dramatically. According to crash physics research, a 50-pound dog generates over 1,500 pounds of force in a modest 30mph crash. An extension tether gives this mass several feet of “excursion” (forward travel) to accelerate. When the tether finally pulls taut, the resulting “snap” applies this enormous force to a single point on the harness and the car’s anchor. This focused load is almost guaranteed to cause a catastrophic system failure: the webbing shreds, the hardware shatters, or the harness itself breaks.

This paragraph introduces a concept complex. To best understand it, it is useful to visualize its key components. The illustration below breaks down this process.

As this high-speed capture demonstrates, the webbing is subjected to forces far beyond its design limits. The Center for Pet Safety’s landmark 2013 study on harnesses explicitly states that extension tethers and zipline products increase the risk of injury by allowing this dangerous momentum to build. A truly crash-tested system integrates the tether directly into the harness, keeping it as short as possible to minimize excursion and engage the car’s seatbelt immediately to begin dissipating energy safely.

Isofix vs. Seatbelt Loop: Which Anchor Point Is Stronger?

A restraint system is only as strong as its weakest link. While consumers focus on the harness, the integrity of the anchor point—where the harness connects to the vehicle’s frame—is equally critical. The two primary methods are looping the car’s seatbelt through the harness or using a dedicated ISOFIX/LATCH system. From a structural engineering standpoint, there is a clear superior choice.

The ISOFIX/LATCH system (Lower Anchors and Tethers for Children) is a set of standardized, rigid anchor bars welded directly to the vehicle’s chassis. These points are specifically engineered and tested for securing child safety seats. As federal safety standards confirm, ISOFIX/LATCH anchors are tested to withstand the immense forces generated in 30mph impacts. When a CPS-certified harness is designed to connect to these points, it creates a direct, robust link to the car’s frame, ensuring predictable performance and maximum strength.

Using the vehicle’s seatbelt as an anchor is a viable alternative, and it is the method used by many certified harnesses. The seatbelt webbing and locking mechanisms are, of course, designed to restrain adult humans. However, the effectiveness of this method depends heavily on the harness’s design and how well it integrates with the seatbelt’s path and locking retractor. An improperly routed seatbelt can introduce slack or create unnatural load points on the harness, potentially compromising the system’s performance in a crash. While strong, it introduces more variables than a direct LATCH connection. Therefore, when available and compatible with your certified harness, the ISOFIX/LATCH points provide a more structurally sound and reliable anchor.

The Front Seat Risk: Why Pets Should Never Ride Shotgun?

The debate about pets in the front seat is often framed around driver distraction. While this is a valid concern— Volvo safety research shows drivers with unrestrained pets are significantly more distracted—the primary reason from a safety engineering perspective is lethally simple: airbags. Placing a pet in the front passenger seat puts them directly in the deployment zone of a supplementary restraint system designed for a 150-pound adult human.

An airbag is not a soft pillow; it is an explosive device. It deploys with incredible velocity, creating a zone of extreme force that is unsurvivable for a pet. The risk is not theoretical; it is a matter of pure physics. A pet, even a large one, does not have the mass or skeletal structure to withstand this impact. The result is inevitably severe or fatal injury.

The dangers are multifaceted and absolute, extending beyond just the front airbag:

- Deployment Speed: Airbags deploy at speeds up to 200 mph (320 km/h), a velocity that will cause catastrophic blunt force trauma.

- Deployment Zone: The front passenger airbag’s danger zone extends approximately 25 inches from the dashboard, encompassing the entire area where a pet would sit or stand.

- Side Curtain Airbags: Even if a pet avoids the front airbag, side curtain airbags deploy with similar force, causing severe lateral impact injuries to any unrestrained body.

- Secondary Impacts: An unrestrained pet in the front seat is also at extreme risk of dashboard impact or windshield ejection, both of which carry a higher severity of injury than a collision with a seat back.

There is no “safe way” for a pet to ride in the front seat. It is a non-survivable environment during a moderate-to-severe collision. The only safe location for a pet is in the back seat, properly secured in a CPS-certified restraint system.

Crate or Belt: Which Is Safer for Large Dogs Over 80 lbs?

As a dog’s mass increases, the forces it generates in a crash grow exponentially. While a certified harness can safely manage a 50 lb dog, the challenge becomes immense for giant breeds. For an 80 lb+ dog, biomechanical testing reveals that a 60lb dog generates 2,700 pounds of force in a 35mph crash; an 80 or 100 lb dog generates well over two tons of force. At this scale, a CPS-certified crash-test crate often becomes the only viable engineering solution for survival.

A harness system works by concentrating crash forces onto the strongest parts of a dog’s body via webbing. A crate works by distributing those forces across the entire rigid structure of the container, which is then secured to the vehicle. This difference in force management strategy is critical for large dogs.

This paragraph introduces a complex comparison. The table below outlines the key engineering and practical differences to help you make an informed decision based on data, not emotion.

| Safety Feature | CPS-Certified Crate | CPS-Certified Harness |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum tested weight | Up to 130lbs (Gunner G1) | Up to 110lbs (Sleepypod Terrain) |

| Containment method | Full structural enclosure | 3-point restraint system |

| Spinal protection | Distributes impact across crate walls | Risk of torso rotation in tall breeds |

| Installation complexity | Requires cargo straps ($100+) | Uses existing seatbelt system |

| Space requirement | Full cargo area or 2 seats | Single seat position |

The data shows a clear divergence in capability. While the best-in-class harness is certified up to 110 lbs, the risk of spinal injury from torso rotation during impact is a significant concern for tall, heavy breeds. A structurally sound, rotomolded crate provides complete containment and protects the spine by absorbing the impact across its walls, a fundamentally safer approach for managing the immense kinetic energy of a giant breed dog.

When to Replace a Safety Harness After a Minor Fender Bender?

The answer is unequivocal: immediately. A crash-tested harness, like a child’s car seat, is a single-use safety device. It is engineered to sacrifice its own structural integrity to save your dog’s life. Even a minor collision at 10-15 mph can generate sufficient force to compromise the materials, rendering the harness unsafe for future use.

The danger lies in invisible damage. During an impact, the high-tensile webbing is designed to stretch to absorb energy, the stitching is stressed to its breaking point, and the metal hardware endures extreme loads. While the harness may appear perfectly fine after the incident, it has likely suffered material fatigue and micro-fractures. The webbing’s fibers may be permanently weakened, and the hardware may have tiny cracks that will lead to catastrophic failure in a subsequent, more severe accident.

This principle is absolute in automotive safety. As the Optimus Gear Safety Team, experts in pet safety science, state:

Like car seats for children, crash-rated harnesses are designed for a single accident. The materials and structure absorb significant force during a collision, which may compromise their integrity. After an accident, it’s essential to replace the harness to maintain safety standards

– Optimus Gear Safety Team, What is Crash Testing? Understanding Pet Safety Science

Relying on a visual inspection is dangerously unreliable. The Center for Pet Safety warns that using a compromised piece of equipment is equivalent to using an untested one; it will likely fail to offer any protection. The cost of a new harness is negligible compared to the cost of equipment failure. Treat any collision, no matter how minor, as the end of your harness’s service life.

Why Harnesses Crossing the Shoulders Restrict Movement?

While crash safety is the primary concern in a vehicle, the ergonomic design of a harness impacts a dog’s health and comfort even when stationary or walking. A common design flaw in many “no-pull” or fashion harnesses is a horizontal strap that crosses directly over the dog’s shoulder points. This design fundamentally misunderstands canine anatomy and can lead to gait restriction and long-term injury.

The key to this issue is the canine shoulder assembly. As biomechanical research confirms, dogs lack a functional clavicle (collarbone). This allows their scapula (shoulder blade) to move with a much greater range of motion than a human’s, which is essential for a powerful, efficient stride. A harness strap that sits across the point of the shoulder physically blocks this natural movement. It pins the soft tissues and underlying structures, preventing the leg from fully extending forward and backward.

This restriction forces the dog to alter its natural gait, often by taking shorter, choppier steps. Over time, this compensatory movement can lead to repetitive stress injuries, muscle imbalance, and joint problems. A properly engineered harness, often called a “Y-harness”, has straps that form a “Y” shape on the dog’s chest. This design leaves the shoulder points completely clear and unencumbered. The pressure is distributed across the sternum, allowing for a full and free range of motion. As canine professionals at Homeskooling 4 Dogs emphasize, “A properly designed and well-fitted harness does not have restrictive straps that sit on top the biceps and supraspinatus tendons. A harness should permit the dog’s legs to have full range of motion.”

From Vomit to Joy: Conditioning a Dog to Ride in the Car

A perfectly engineered restraint system is useless if the dog is too panicked or nauseous to tolerate it. Car anxiety and motion sickness are common issues that stem from negative associations or a sensitive vestibular system. Solving this requires a systematic process of counter-conditioning and desensitization, transforming the car from a source of stress into a neutral or even positive space.

The goal is to break the cycle of fear. This is not achieved by forcing a dog into the car for a trip to the park, as this can amplify the initial anxiety. Instead, it requires a gradual, patient protocol that rewires the dog’s emotional response. The process involves isolating each component of car travel—the car itself, the doors closing, the engine starting, and finally, movement—and pairing it with high-value rewards until the dog is calm and comfortable at every stage. This methodical approach ensures the dog is never pushed past its emotional threshold.

For a dog suffering from motion sickness, trainers also report success with “scent anchoring,” where a calming pheromone or a familiar blanket is used exclusively for car training. This creates a predictable, safe-feeling environment that can help override the negative physical sensations. The key is patience and consistency.

Action Plan: A Protocol for Car Anxiety Desensitization

- Stationary & Open: Begin by simply sitting with your dog in the stationary car with all doors open. Reward calm behavior like sitting or lying down with high-value treats. Keep sessions short (1-2 minutes).

- Doors Closed: Once comfortable, practice closing the doors for a few seconds, then opening them and rewarding. Gradually increase the duration the doors remain closed while you remain inside with the dog.

- Engine On: With the dog calm with the doors closed, start the engine for a few seconds, then turn it off and reward. Do not move the car. The goal is to neutralize the sound and vibration of the engine.

- Minimal Movement: Once the engine sound is neutral, reverse down the driveway and immediately pull back in. This initial movement should last less than 30 seconds. Reward heavily upon stopping.

- Gradual Increase: Slowly build on this foundation by driving around the block, then for a few minutes, always ending on a positive note before the dog shows signs of stress. Monitor for stress signals like yawning, lip licking, or panting.

Key Takeaways

- Physics is Non-Negotiable: A dog’s weight multiplies into thousands of pounds of force in a crash. Equipment must be engineered to manage this, not just to restrain a calm dog.

- Extension Tethers are a Death Trap: Any tether that allows for slack creates a slingshot effect, guaranteeing catastrophic equipment failure at the moment of impact.

- Certification is the Only Standard: “Safety” is a marketing word. “Center for Pet Safety (CPS) Certified” is an engineering standard proven through independent crash testing. Accept no substitutes.

Y-Harness vs. No-Pull: Which Prevents Shoulder Injuries in Pullers?

The harness market is broadly split into two philosophies for walking: standard Y-harnesses that are neutral pieces of equipment, and “no-pull” harnesses that actively alter a dog’s movement to discourage pulling. While no-pull harnesses can be effective training aids, from a biomechanical perspective, many designs—particularly those with a front clip or a horizontal chest strap—pose a risk of creating long-term gait abnormalities and shoulder injuries.

As a recent study into the effect of harness design on the biomechanics of domestic dogs notes, the impact of different designs is a critical but often overlooked area of canine welfare. The fundamental difference lies in how they interact with the dog’s body when the leash is tight. A Y-harness distributes pressure across the dog’s sternum, allowing the shoulders to move freely. A front-clip no-pull harness works by redirecting the dog’s forward momentum sideways, twisting their torso and pulling their shoulder offline. This unnatural lateral force can alter gait and, over time, lead to compensatory injuries.

The following comparison breaks down the biomechanical impact of these two common designs, providing a clear framework for choosing equipment that prioritizes long-term physical health.

| Feature | Y-Harness Design | Front-Clip No-Pull |

|---|---|---|

| Shoulder blade clearance | Full clearance of scapula | Potential scapula restriction |

| Gait alteration | Minimal to none | Redirects momentum laterally |

| Pressure distribution | Across chest plate | Concentrated at attachment point |

| Long-term injury risk | Low when properly fitted | Potential for compensatory injuries |

| Training effectiveness | Neutral equipment | Active training tool |

The evidence points to the Y-harness as the superior choice for everyday use and for any activity involving movement, as it does not interfere with the dog’s natural biomechanics. A no-pull harness should be viewed as a temporary training tool to be used under guidance for specific pulling issues, not as a permanent piece of walking equipment. For the health of your dog’s shoulders and spine, a harness that allows for an unrestricted, natural gait is always the correct engineering choice.

Your next step is not to find a “better” safety harness, but to discard any non-certified equipment and invest in a system proven to manage crash forces. Verify the product on the Center for Pet Safety’s official certification list. For the survival of your pet, there is no other acceptable standard.